Michael Ruse, author of the book Defining Darwin, Essays of the History and Philosophy of Evolutionary Biology, concluded that “Indeed, the truth is that there is virtually nothing today in evolutionary studies that correspond exactly to the facts of the Origin.” Molecular clocks are one example.

Michael Ruse, author of the book Defining Darwin, Essays of the History and Philosophy of Evolutionary Biology, concluded that “Indeed, the truth is that there is virtually nothing today in evolutionary studies that correspond exactly to the facts of the Origin.” Molecular clocks are one example.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the idea of molecular clocks was not even remotely considered, not to mention cellular biology or DNA. The scientific revolution had yet to reach into the realm of molecular biology. Case-in-point, Darwin thought “gemmules” learned by parents were passed on to the next generation through a process of “blending inheritance.”

Today, we know that “gemmules,” whatever they were thought to be, do not learn; it was a fabricated idea. And ironically, blending inheritance was soon recognized as an argument against Charles Darwin’s theory. Without a mechanism of inheritance, interest in Darwin’s theory by the end of the nineteenth century nearly vanished.

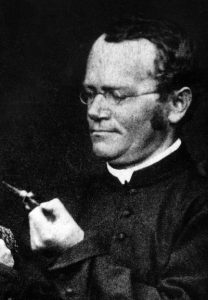

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel

In 1865, Gregor Mendel (pictured right), an Austrian monk, discovered the genetic laws of inheritance. Studying the biblical account of Jacob’s selective breeding program of “speckled and spotted sheep… the brown ones among the lambs, and the spotted and speckled among the goats” in Genesis, may have influenced Mendel.

While decimating Darwin’s theory of “blending inheritance,” Mendelian genetics, also known as Mendelian inheritance, in turn, saved Darwin’s theory, it seemed. But it took time.

Not until decades later were Mendel’s laws of inheritance rediscovered by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns in 1900. Mendel’s theory was presented as Darwin’s new mechanism of inheritance. Evolution’s missing key was at last found, it seemed.

Molecular biology quickly gained center stage in the race to trace and validate the steps of Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Still, nearly fifty years elapsed until the molecule of inheritance, DNA, was scientifically validated.

The Pace of Evolution

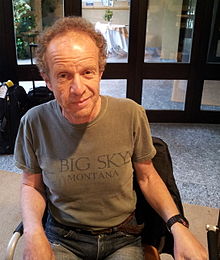

Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling

To gain an estimate of the pace of evolution, in 1962, molecular biologist Emile Zuckerkandl and Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling at the California Institute of Technology proposed developing a new field of investigation they called “molecular anthropology.” To be more definitive, the name was subsequently changed to “molecular clocks.”

Zuckerkandl and Pauling (pictured right) proposed that molecular changes would occur at a constant rate during the evolutionary process of speciation. The pace of these molecular changes, it was thought, held the secret keys to the rate of evolution.

Initial problems were thought to be biotechnical, not problems with the theory. As evidence continued to accumulate through the early 1990s, however, it became increasingly apparent that the theory was intrinsically problematic.

But that is not all. While the essence of Darwinian evolution is characterized by “slight, successive” changes, even finding these changes between closely related species emerged as a tricky business.

Differing Rates

The first emerging issue was the constant rate problem. Not only were rates found not to be constant, but different molecular clocks were often found running even within the same species. In 2007, Naoyuki Takahata, of The Graduate University for Advanced Studies in Japan, published in the journal Genetics, addressed the problem in the article Molecular Clock: An Anti-neo-Darwinian Legacy, stating –

“It is now clear that any kind of molecular clock ticks erratically.”

Since Zuckerkandl and Pauling’s simple postulate seemed to be more complicated than expected, it begs the question, are molecular clocks real? Professor of evolutionary biology Thomas Cavalier-Smith of the University of Oxford in England, cut-to-the-chase. In the article published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society entitled Cell Evolution and Earth History: stasis and revolution (2006), he said –

“Evolution is not evenly paced and there are no real molecular clocks.”

Within the evolution industry, the idea of molecular clocks has created chaos rather than consensus. For Michael S. Y. Lee, in the article Molecular Clock Calibrations and Metazoan Divergence Dates (1999) published in the Journal of Molecular Evolution –

“Unfortunately, molecular clock studies have yet to provide a set of rigorous criteria for justifying which fossil dates are to be used in calibrations and which are to be treated with skepticism.”

Italian geneticist Giuseppe Sermonti (pictured right) noted in his book entitled Why a Horse Is Not a Fly (2005).

“Once the universal ‘molecular clock’ was shelved, biochemists ceased to question (in any case dubious) datings proposed by paleontologists.”

Eugene V. Koonin, Senior Investigator for the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), argues in his book The Logic of Chance, the Nature, and Origin of Biological Evolution (2011) –

“Subsequent tests of the molecular clock hypothesis on the growing sequence collections showed that, for most genes, the clock does not click at a constant rate; instead, the clock is significantly over-dispersed − that is, the variance of the evolutionary rates substantially exceeds the random variation predicted for a Poisson process.”

“Perhaps a ‘molecular clock’ approach might work…,” argued British journalist John Archibald in his book One Plus One Equals One (2014), published by Oxford University Press, “[but] the results were problematic, to say the least.”

Implications

Since Zuckerkandl and Pauling understood Darwin’s theory of evolution should be the result of “slight, successive” changes over long periods of time, they concluded that molecular biology, therefore, should reflect these changes over time at a constant rate.

During the late twentieth century, biotechnological advances finally gave scientists the tools to test Zuckerkandl and Pauling’s theory. The evidence, it is now known, has invalidated their theory. Darwin’s “slight, successive” changes over long periods of time are not supported by biomolecular evidence.

Contrary to initial expectations, molecular biology has yet to validate Darwin’s theory of evolution. In the words of Darwin in the Origin of Species –

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ exists which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.”

Evolution continues as a philosophy, not as a scientific fact. Using Darwin’s criteria, his theory has “absolutely broken down.”

Genesis

Starting with Darwin’s publication of the Origin of Species in 1859, following more than a century of investigations, valid scientific explanations for the origin of life continue to be compatible with the Genesis record as written by Moses.

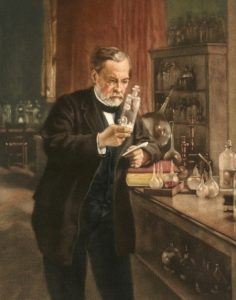

Louis Pasteur (pictured right), a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, also credited for disproving Darwin’s once-popular theory of spontaneous generation, realized during the Scientific Revolution that –

“The more I study nature, the more I stand amazed at the work of the Creator.”

Biological evolution exists only as a philosophy, not as a valid scientific theory.

Refer to the Glossary for the definition of terms and to Understanding Evolution to gain insights into understanding evolution.